Most writers research their books before they write them, but my muses are independent thinkers. I wrote Coyota first, then, in a perverse desire to see if I’d done a competent job of writing the Mexican scenes, I concocted The Mexican Magical Mystery Book Tour, although it was much too late to change the book.

Carol Eastes, Editor & Chief of Papalote Press, was willing to be my roadie, helping schlep books, set up events, and quality control the guacamole. Her job required a great deal of altruism as circumstances forced us to dine frequently on mole enchiladas, churros, and homemade coconut ice cream, as well as absorb daily doses of vitamin T—that’s tequila—usually in the form of margaritas. ¡Pobrecita!

Our schedule revolved around being in San Miguel de Allende to witness the town’s legendary New Year’s Eve festivities—a blow-out I’d never experienced, but had brazenly written about anyway in Coyota, with the help of a San Miguel resident I’ve yet to meet.

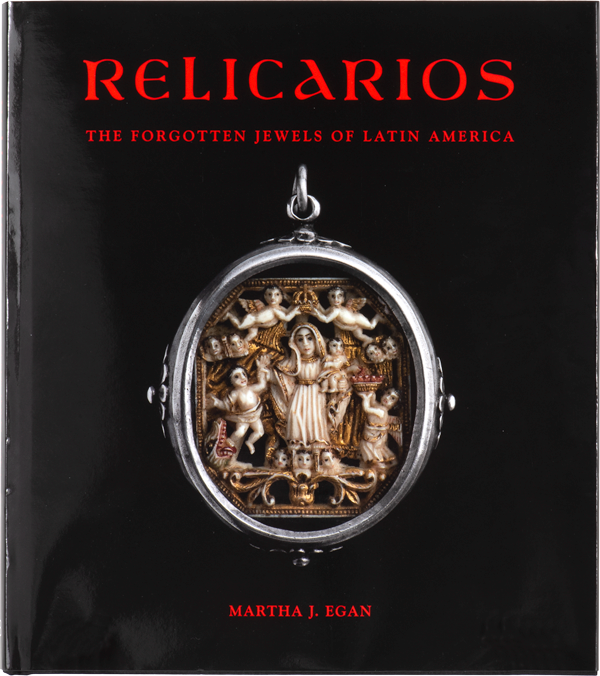

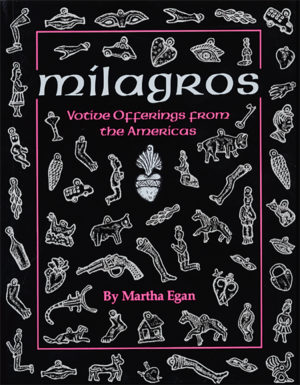

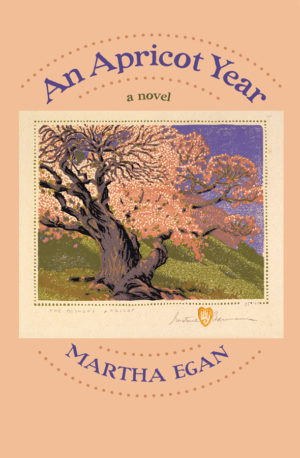

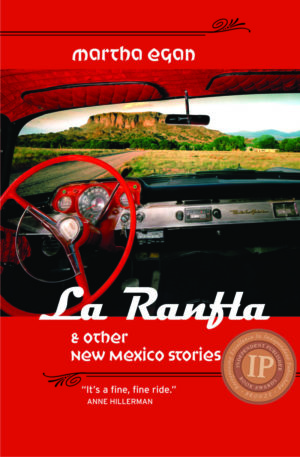

The day before New Year’s Eve, I signed all four of my books for visitors and local characters at Zócalo, Deb and Rick Hall’s wonderful folk art store in the heart of San Miguel. Friends from Mexico City, Frances and Guillermo Echeverría, supplied the essential Mexican part of the Magical Mystery Book Tour. That night, we all repaired to the Halls’ home to tour their collection of folk art, enjoy a delicious posole supper, and meet their xoloitzcuintle hairless dog.

On New Year’s Eve, Francis and Guillermo prepared a Spanish style late evening supper for us in their hotel room: olives, cold meats, fresh baguettes, and various cheeses, accompanied by a bottle of Gruet’s Blanc de Noirs champagne and Señor Murphy’s chocolates that I’d brought from New Mexico. We each ate 12 grapes for good luck, though well ahead of midnight, when it is customary to eat a grape with each ring of the tolling church bells.

Thus fortified for the adventure ahead, we walked the festively decorated cobblestone streets to the Jardín, San Miguel’s principal plaza, to wait in front of the wedding-cake gothic pink Parróquia church. The plaza was packed, alive with local families, and tourists— Mexican and gringo alike, some in evening clothes, some dressed as clowns. It’s a Mexican tradition to wear red underwear for good luck on New Year’s Eve, but happily no one was checking. A lively sonora band at one side of the church inspired revelers to dance to its heavy tropical beat. From other corners of the plaza, mariachi bands competed, the blasts of their trumpets and melodious male voices reverberating off the colonial buildings.

New Year’s Eve in front of the Parróquia is not for the timid. Party-goers should definitely have their life and health insurance paid up. The fireworks are set up not on some distant hillside as they would be in the lawsuit-conscious US, but hanging off the church spires almost overhead. On a corner of the plaza, a forty-foot-high castillo, a rickety-looking traditional Mexican “castle” of bamboo and fireworks, was ready to go. Everyone brandished sword-length sparklers they bought from strolling vendors–three for ten pesos, about 30 cents apiece. Year and a half old identical twin girls dressed in matching pink snowsuits held sparklers taller than they were. In that child’s trance of terror and delight, they watched them cast off fiery glitter. Behind me, a hearty partier in a tux swilled Moët et Chandon out of the bottle and waved his drooping sparkler over my head, shedding a rain of sparks. I thought my hair would ignite. Didn’t he wonder why I kept hitting myself on the head? And why wasn’t he sharing the champagne?

As midnight drew closer, the crowd became more boisterous and excited. Cohetes—bottle rockets—whizzed and screamed into the sky, bursting into flashes of light and ear splitting booms. Strings of firecrackers rat-tat-tatted like machinegun fire. When the clock struck twelve, the plaza erupted, everyone shrieking and enveloping each other in abrazos and kisses, wishing friend and stranger alike “¡Feliz Año Nuevo!”

From all over town, church bells rang madly. Fusillades of fireworks lit up the night directly overhead in jewel colors, dropping debris on our heads. The castillo blazed, its whirring, whirling pinwheels crazily shooting flames, fireworks, and embers into the crowd. Oblivious, people stood around it, happily taking pictures with their pocket cameras and cell phones through a haze of gunpowder smoke. The pyrotechnic pandemonium in the plaza was like a conflagration in a fireworks factory.

Too soon, flames of the Castillo dissolved into flickers of light, the last fireworks exploded, and in a scene worthy of a Fellini movie, the clowns’ makeup ran down their faces. Parents hoisted exhausted kids onto their shoulders, the price of sparklers slid to ten for ten pesos, and the crowd slowly dispersed. Suddenly, it was January 1, 2008.

So did I get the New Year’s Eve scene right in Coyota? Actually, the Jardín was even wilder than I described it. Did any sinister DEA agents like those in the novel follow us around San Miguel? A husband and wife pair of local cops were at breakfast every morning in our wonderful pensión, but they were charming and told interesting stories.

In Coyota, the main characters drive to Guanajuato after the New Year’s bash, and so did we, in a taxi filled with books, loot from our shopping expeditions, luggage, and our well-fed selves.

Guanajuato is a Unesco World Heritage Site, an hour and a half from San Miguel, home to the Cervantes Culture Festival each October, and birthplace of Diego Rivera and his twin brother. Wealthy silver mine owners lavished their fortunes on baroque churches, baronial palaces, and the Teatro Juárez Opera House, now fully restored to all its eclectic, riotous glory. The Estrella de la Valenciana Inn, our comfy residence in the hills above Guanajuato, was the best place to view the city nestled below in a chalupa-like bowl formed by the folds of surrounding mountains.

The city’s labyrinthine streets, once mining tunnels, burro paths, and rivers, were the perfect setting for the madcap car chase in Coyota, which I read to a respectable turnout of Mexicans and ex-pat Americans at Fernando and Ana León’s well-appointed folk art and bookstore, Mi Viejo Zaguán. The Leóns had papered Guanajuato with handmade flyers and had decorated their store for the event.

For the next event, we traveled to the colonial city of Pátzcuaro, a four-hour cab ride into the state of Michocán, Mexico’s breadbasket, a land of rolling fields and lakes. Here, in the Halls’ second Zócalo gallery, two-dozen enthusiastic guests enjoyed my reading, asked a few questions, and bought books. I spent most of the proceeds on Zócalo’s folk pottery for my retail store, Pachamama.

Before we left Pátzcuaro, Deb Hall treated us to a shopping blitz. On the run, we toured the delightful Folk Art Museum, bought shawls at the Tuesday market, and visited my favorite silversmith, Jesús Cáceres, in his cell-like workshop. A beautiful pair of his traditional Purépecha earrings went directly onto my ears.

That night we arrived in Ajijic, a beautiful little town on the shore of Lake Chapala, for my final book event of the tour. Our hostess, Marianne Carlson, showed us an article in the local English language newspaper that said I offered to buy “free drinks” for all who attended my book signing at the Nueva Posada Hotel. Oops! I mean fruit aguas, not martinis!

Worse yet, the hotel’s cook was miffed that no one had told her about the event. I pacified her with a box of Señor Murphy Twin Peaks, and on the spot, she prepared aguas and a tureen of fabulous guacamole with totopos. Ah, the power of chocolate! The people who came, many of them writers, were simpático. The legions of thirsty, scruffy drunks I envisioned showing up to hold me to my “promise” never appeared.

We enjoyed a farewell dinner the following evening in a posh hillside palapa restaurant with a spectacular view of the lake at sundown. The English menu was enchanting. Sample: “Stuffed shrimp of cheese and silverware of bacon, on a mirror of sauce of tomato, areas of bathed with a sauce of guajillo with grains of natural sweetcorn and julienne of peppers.” I wasn’t sure what I was eating, but it was delicious.

The Mexican Magical Mystery Book Tour had come to an end. When you run out of clean underwear, it’s time to go home. Like Johnny Appleseed, we left many books behind and hope they’ll sprout to make the rounds of English readers.

I’ll have to write more about Mexico so we can do this again.